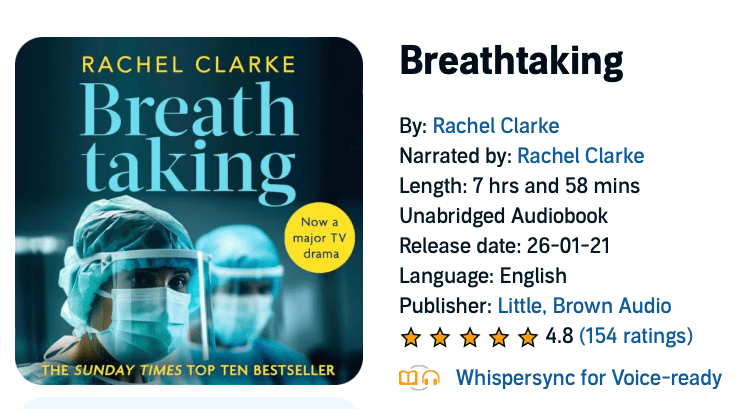

My current listening. I forget to breathe.

Some quotes below, offered as fair use of copyright material of the author Rachel Clarke (transcribed from the audiobook read by the author herself)…

Chapter 1: Pneumonia of Unknown Cause

20:00

In January 2020, novel coronaviruses are nowhere on my mind. Like everyone working in the NHS, I’m steeled for a home-grown catastrophe. For no matter how many patients lie on trolleys in corridors, how many ambulances sit trapped on hospital forecourts, how many photos go viral of toddlers slumped on their parent’s coat, receiving oxygen on the floor of a beleagured A&E, nothing ever truly changes.

These days the annual NHS winter crisis is both dreaded and reliable as clockwork. The numbers are so large, and repeated so frequently, they have long been leeched of their force. 17,000 hospital beds lost since 2010. Only 2.5 beds per thousand people in the UK, compared to three times that number in Germany, and an NHS workforce so depleted it has unfilled vacancies for over 10,000 doctor and 40,000 nurses. And in Social Care (the NHS’s much neglected and impoverished sister) an eye-watering 120,000 unfilled vacancies.

Yet underlying these statistics are of course individuals. Patients: people at their most exposed and vulnerable. NHS staff dread winter because nothing quite so curdles the soul like pouring your all into a system at breaking point.

Chapter 3: Worst-Case Scenarios

Boris Johnson: asked on live TV about his personal policy on shaking hands

I’m shaking hands continuously. I was at a hospital the other night where I think there were a few coronavirus patients and I shook hands with everybody, you’ll be pleased to know, and I continue to shake hands.

18:45

In ten seconds Johnson has torpedoed the efforts of his scientific advisers to appraise us of the gravity of the situation. Apparently all you need to face down coronavirus is oomph and bravado. No need to overreact, folks.

In times of uncertainty we rely, do we not, on our leader’s lead. The PM has only recently chosen to spend a Saturday afternoon watching the England v Wales Six Nations International, alongside 82,000 other rugby fans crammed into the stands at Twickenham. It generates approving headlines from some of the press: Boris Johnson Braves Coronavirus Outbreak With Pregnant Fiancee To Support England –in the Daily Express, for example. But many doctors, myself among them, are distraught at the symbolic defiance. Official medical guidance not to shake each others’ hands and keep a cautious distance means nothing when the PM himself ignores it.

Chapter 7: Inside the Wave

27:55

The term moral injury was first used to describe soldiers’ psychological responses to their actions in war. “Potentially morally injurious events, such as perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations, may be deleterious in the longterm, emotionally, psychologically, behaviourally, spiritually and socially” states a 2009 paper in the Clinical Psychology Review. In healthcare, the crux of moral injury is a practitioner’s sense that they are failing consistently to meet their patient’s need, often due to systemic factors beyond their control. Such as, in this case, the dehumanising consequences of rigorous infectious control. The sense of complicity in providing inadequate or inhumane care can lead to well-documented feelings of guilt and anguish.

Anyone who works within two metres of patients, irrespective of whether a patient is infected with covid, must wear Level 1 PPE. At a minimum this constitutes a fluid-resistant paper mask; an apron; gloves; and – if the risk of splashes is significant – a visor too.

New belated Government Guidance

There is just one snag with the guidance, which I note still falls short of the WHO’s minimum standard. Any non-hospital clinical setting, be that a care home, a general practice, or a hospice, had been issued with the same standard PPE pack. It contains a roll of plastic aprons, some gloves, and a box of 300 paper face-masks, some of which have a best-before date of 2016.

To put the inadequacy of these supplies into sharp relief: at the Katherine House Response Centre we are estimating a daily requirement of at least 150 masks. But, at precisely the time we are reconfiguring the hospice at breakneck speed to admit patients dying of covid, the Government has provided us with a stock of masks that will last, at most, for two days.

You might as well push a passenger out of a plane with a handkerchief in lieu of a parachute.

35:44

“What about the emergency PPE line?” I ask Charlie in confusion. “Haven’t they been able to sort it?”

After the slew of negative headlines about desperate NHS staff using bin bags, honemade visors and builders’ masks for protection, the government has hastily announced a new 24/7 emergency NHS supply chain hotline. This, we’ve been assured with much public fanfare, will enable any health or care teams in crisis to obtain urgent supplies of PPE. Naively I’d imagined some kind of superhero hybrid of Matt Hancock and the batphone: one call and a caped crusader would instantly swoop to our rescue.

The reality is jarring.

38:40

“Can I make sure I’ve understood this accurately?” I say to Charlie, endeavouring to keep my voice level. “If we cannot get a delivery of masks tomorrow for the staff to wear – basic paper masks – we’re going to have to close the hospice and send all our patients away? Some of whom are actively dying in the final days, or even hours, of their lives?”

He nods helplessly.

Central to all of this is making sure that we protect the vulnerable. The highest risk groups are the elderly and those with pre-existing illnesses, and those are the ones we’ve got to take most care to protect during this.

Sir Patrick Vallance: on live TV

43:45

If those really were the intentions, how has it come to this, a month later? That each of the nation’s 30,000 care homes has been given nothing more than a two-day supply of masks apiece, forcing upon staff the impossible choice of abandoning their residents, or going to work unprotected.

I understand and agree that if PPE is scarce it should be conserved for our colleagues in the highest-risk areas. But to pretend, as the government is doing, that there is sufficient PPE to go around is spectacularly dishonest.

Staff are scrambling around to do the best we can with what we have. But the reality is: we do not have enough. Our best is barely up-to-scratch. Patients and staff are being endangered. And we have had since January to procure the PPE that should, even now, be protecting 400,000 of Britain’s most vulnerable citizens from a virus we have known all along may kill them.

46:22

It’s abundantly clear that our patients were no one’s priority. No one in power had properly considered them. There is a hierarchy to dying, as with everything else, and those approaching the end of their lives, whether through extremes of age, or a life-limiting illness, are evidently at the bottom.