Playing with ChatGPT recently, to compose folk tales, I’ve been struck by its ability to convincingly flesh out the story to whatever length you ask for. From the bare outline of a folk tale, it comes up with rich and plausible detail. Where is all this stuff coming from?

It turns out that’s the wrong question to ask. The training set is no longer present in ChatGPT – an Artificial Neural Network (let’s call it an NN). Only the strengths of the interconnections of its neurons. Just as with a picture of Taylor Swift on TV, Taylor is not present inside the TV set. There is only the brightness and hue of every pixel on the screen.

A Google blog from 2015 explains all this perfectly to me, and in simple terms. This is two years before the famous paper Attention is all you need, which laid the foundations for Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPTs), ChatGPT, and the fashionable Large Language Models (LLMs).

The authors are investigating an NN trained to spot features in photos. Examples: what animal/bird/object is this? Does this landscape contain a battletank? (The military are keen to know.)

The NN contain 10-30 layers (think: levels of management in a corporate hierarchy). Each layer talks to the next layer, starting with 1: the input layer (think: the sales force) to 10: the output layer (think: the CEO – this is my metaphor, not the authors’), extracting higher and higher levels of detail.

Thus 1: the input layer, will show the original picture. The next layer, 2, will tend to register lines and their orientation.

The final, or output, layer (the CEO) may then shout: “bananas!”.

Now nobody wants to create a monster ai without knowing what’s going on inside it. So here’s the challenge: visualise (e.g. draw an image of) what’s going on in each layer, to check it’s properly detecting what you hope.

One way of doing this is: turn the network upside down and ask each layer to enhance whatever it “sees” whenever you show it a test image. You can do this by applying the given layer (viz. its algorithm) over and over again, which amplifies whatever it is that it detects.

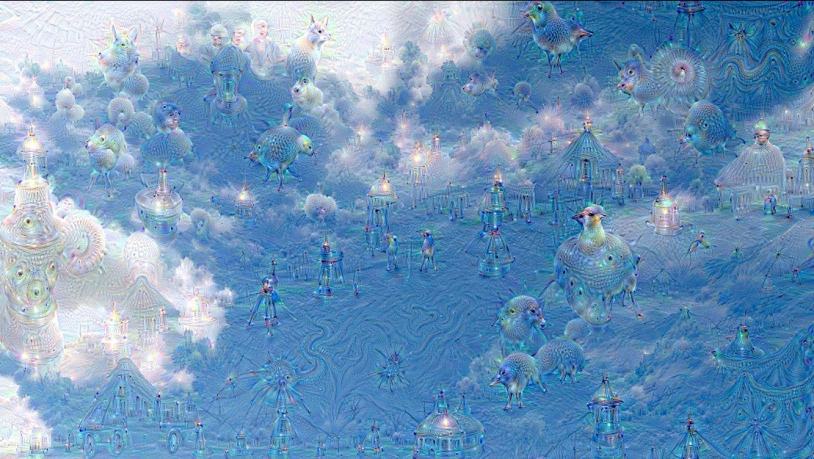

We ask the network: “Whatever you see there, I want more of it!” This creates a feedback loop: if a cloud looks a little bit like a bird, the network will make it look more like a bird. This in turn will make the network recognize the bird even more strongly on the next pass and so forth, until a highly detailed bird appears, seemingly out of nowhere.

The authors call this process inceptionism. The article, plus the Google gallery it references, shows charming pictures of given layers doing exactly that. To me that’s like nothing so much as crystallisation from a saturated solution, an almost magical process I’d only ever seen in chemistry classes.

One such picture of a given layer’s response to a screen of white noise – a sort of visual “hiss” – shows a mish-mash of dumbells, an object in the training set. However each dumbell has an arm attached. The NN never saw a dumbell without an arm holding it, so it inferred the arm was an essential component.

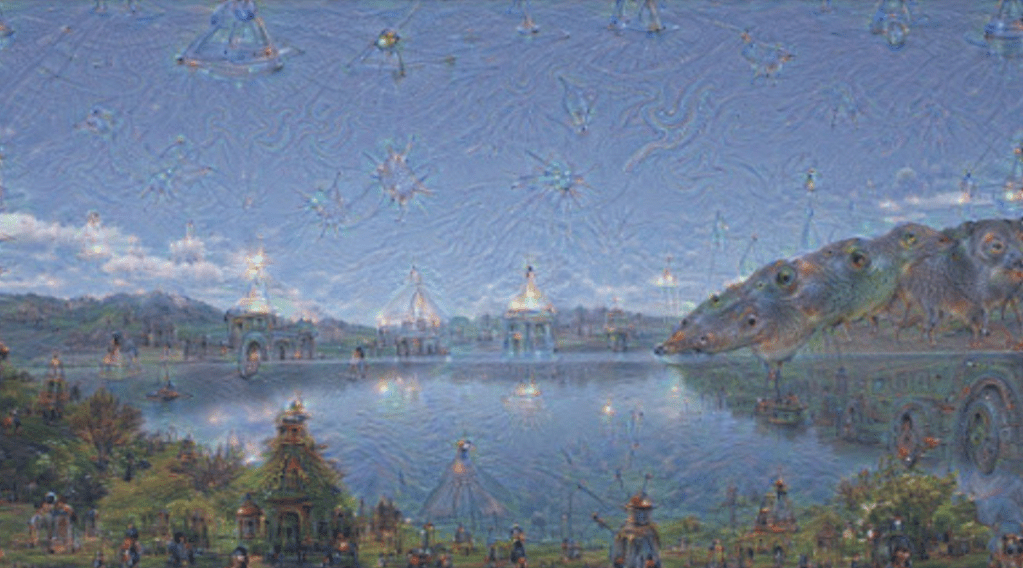

Other examples show the NN hallucinating objects from its training set, populating the sky with miscellaneous objects, the horizon with towers and pagodas, rocks and trees turning into buildings…

… the original picture, which becomes…

The final paragraph of the article is stunningly prescient, predicting the impact of DALL·E, (now a ChatGPT bolt-on feature):

It also makes us wonder whether neural networks could become a tool for artists—a new way to remix visual concepts—or perhaps even shed a little light on the roots of the creative process in general.