I’ve long wanted to chat with ChatGPT in a more concise way. But still in a precise way, to be sure of what I’m getting. After all, how can you trust the oracle’s answer if you can’t be sure how your question’s been taken?

This was the problem with the Delphic oracle of old. Remember poor old King Croesus? According to Herodotus, the Delphic oracle told Croesus: “If you cross the river, a great kingdom will be destroyed.” Croesus thought this meant he’d have the victory over the Persian Empire. But, as it turned out, the kingdom destroyed was his own.

So I’ve been evolving a way of talking to ChatGPT which helps me trust the answer more. Trained as an algebraist, this means to me a mathematical way of putting my questions.

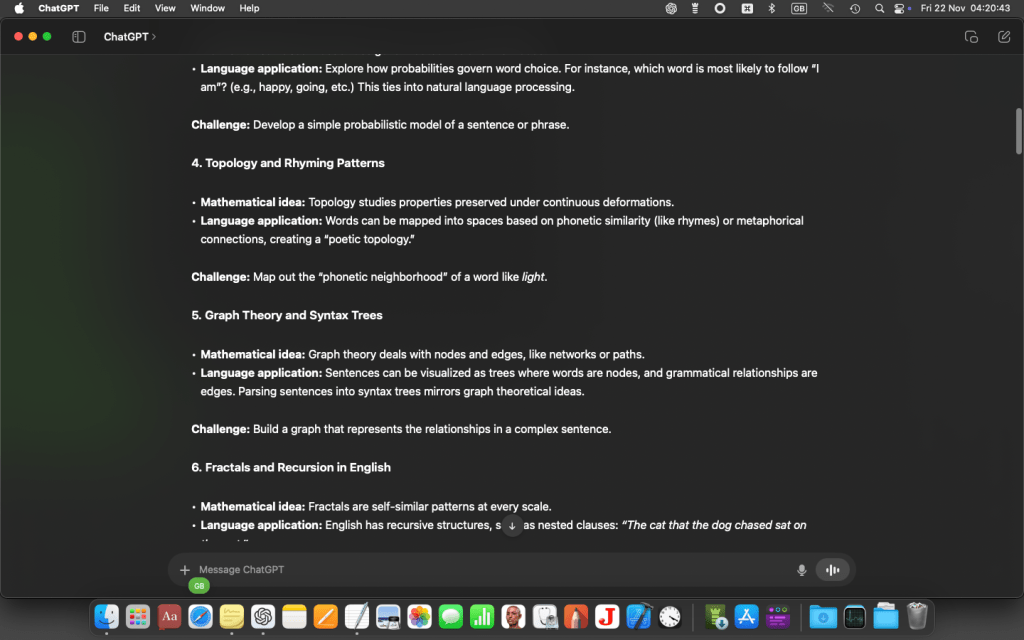

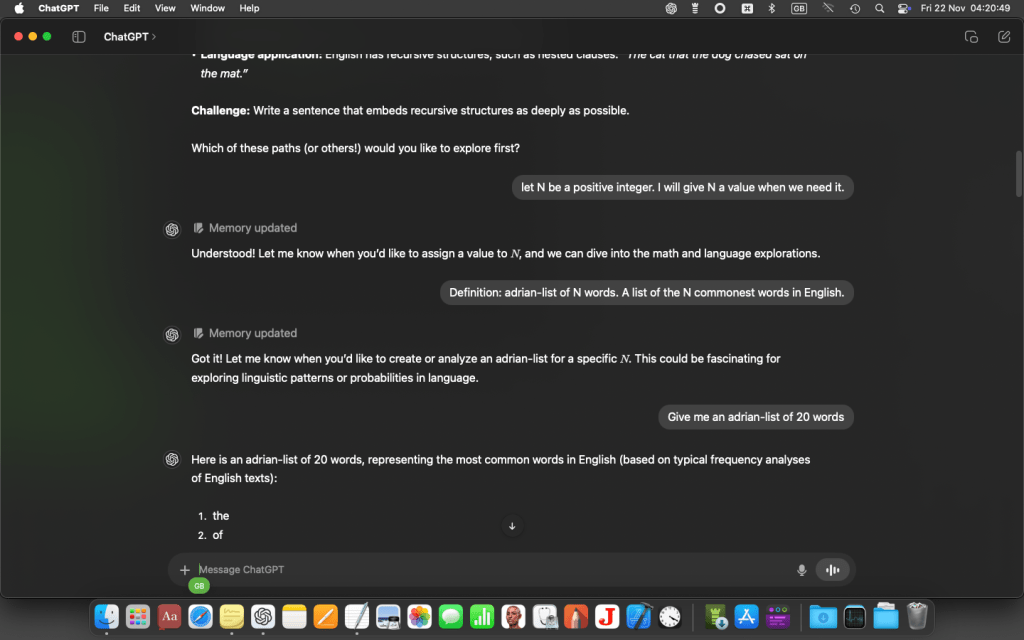

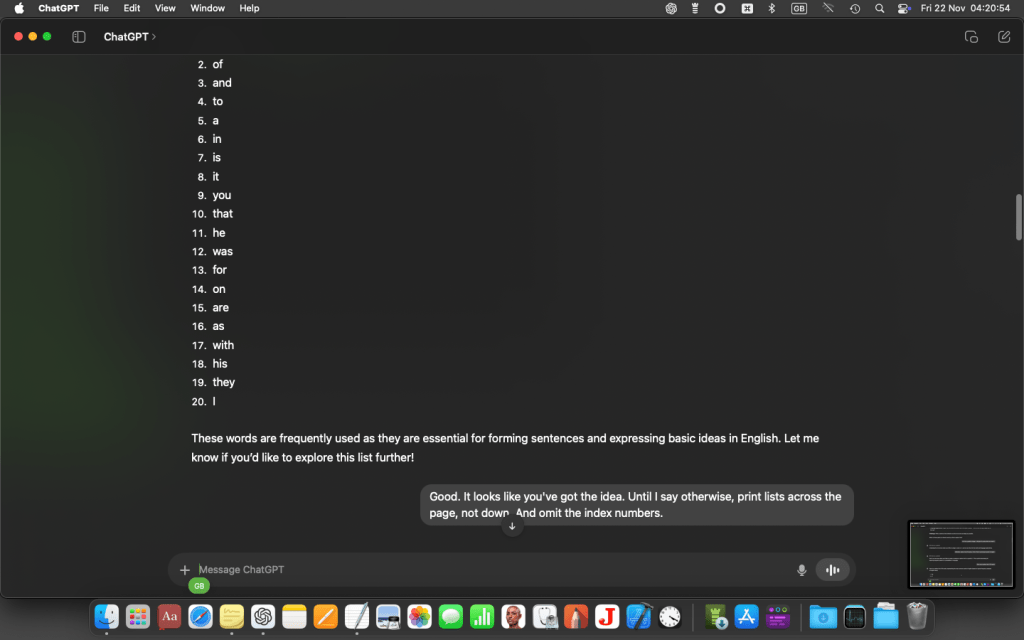

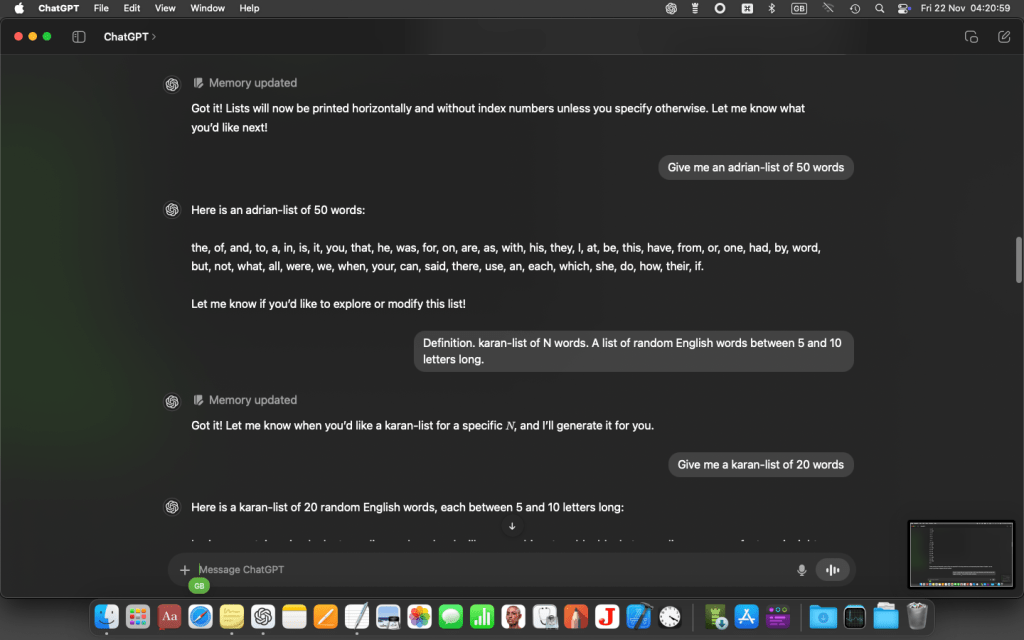

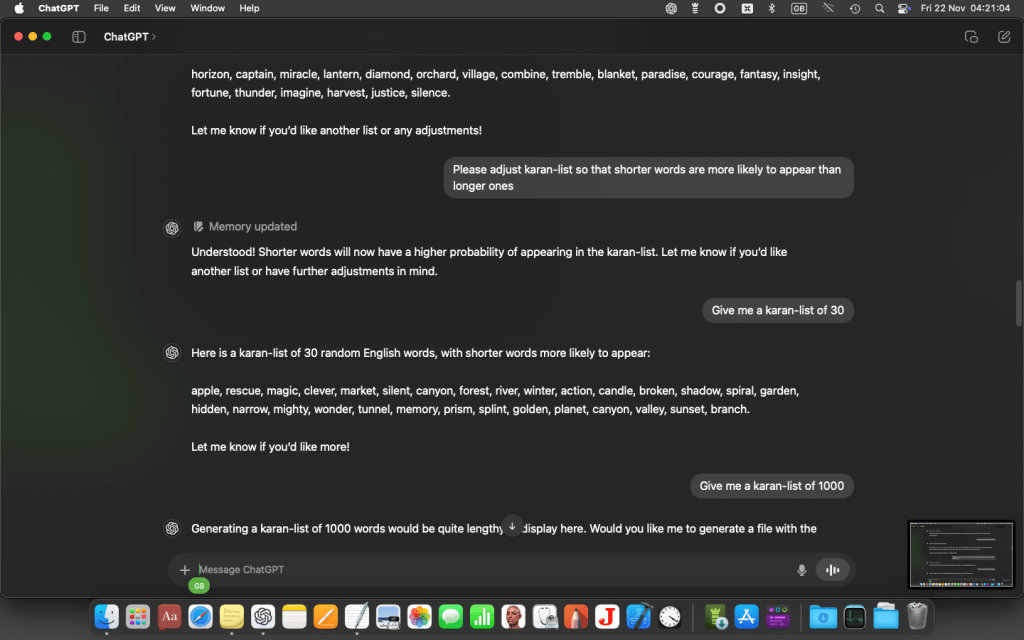

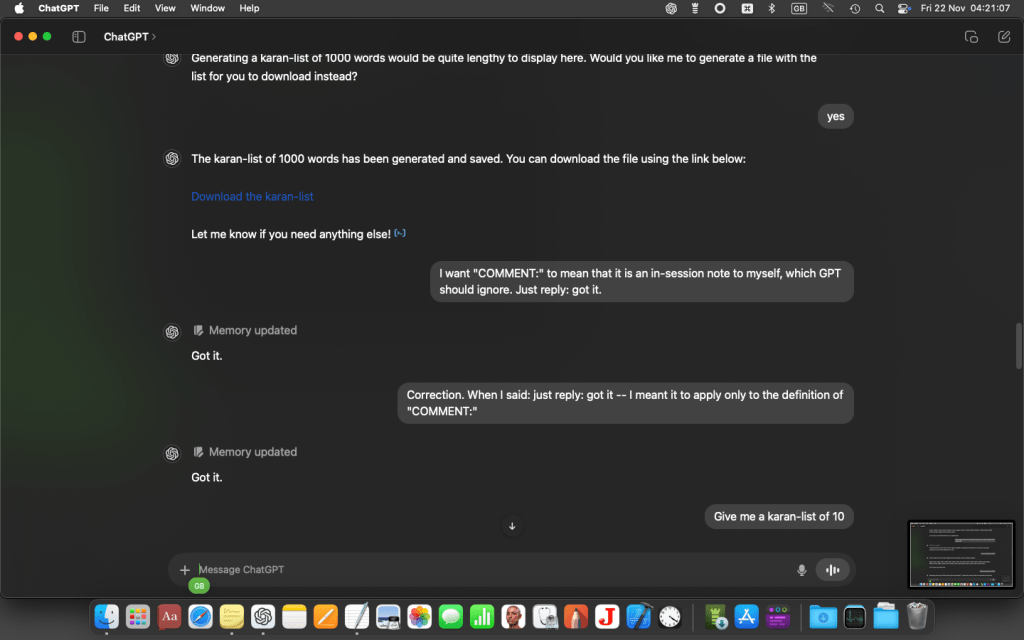

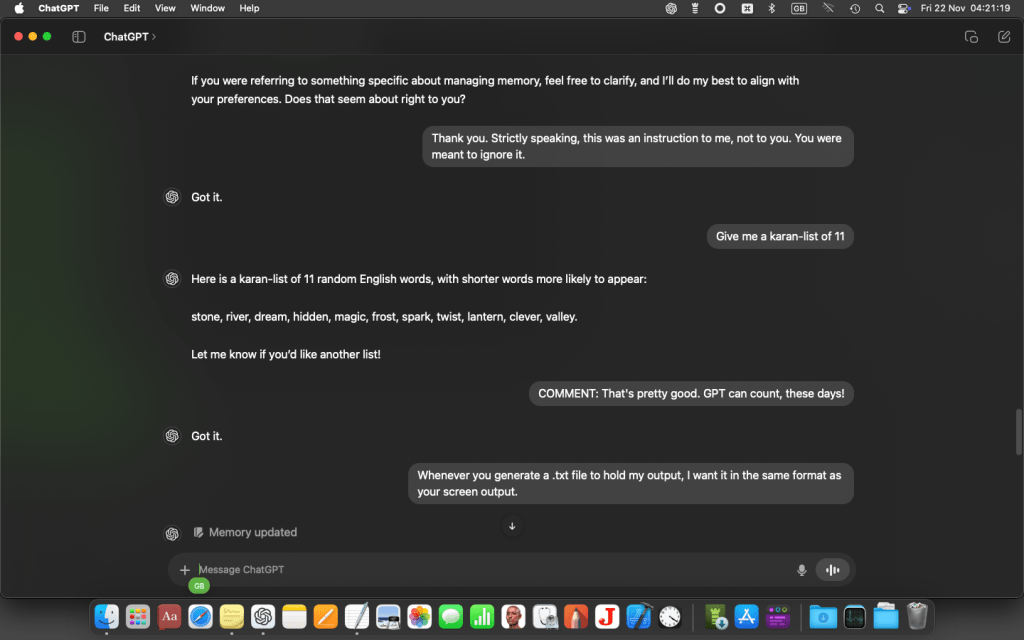

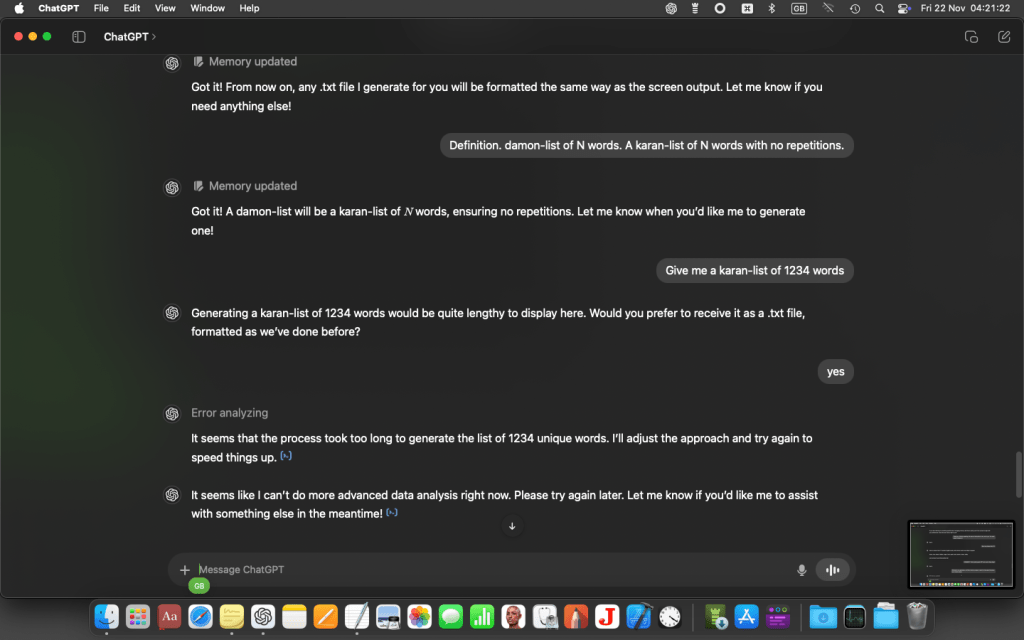

Here’s a screen-dump of a surprisingly helpful session, which gets me near my goal.

(You may need to “zoom in” now, i.e. make the browser text bigger to read the screenshot.)

Okay, the serious stuff starts here.

NOTE: GPT remembers what’s been said. But hitherto, only within the scope of a single session. Now you can extend its memory to future sessions. But you can have too much of a good thing, so the memory feature can be switched on and off. When switched on, it’s good to know precisely what things it is remembering, and to be able to bin them at need. The “Memory updated” message warns you when you might want to do this.

At this point I got a message from GPT o4 saying I’d exceeded my free allowance for the day, and it was automatically downsizing to the cut-down version. (This wouldn’t happen if I’d had a paid-for subscription on macOS.) But I carried on with the cut-down version (mini-o), which proved good enough…

I wonder if the problem I’m having with ChatGPT doesn’t stem from having been a longtime power-user of computers. I want to chat with the precision I’m familiar with. But ChatGPT wants to read my mind and do what I mean. Or: what it thinks I mean.

Or should that be: what I think it thinks I mean?

Clearly if we go psycho-analysing each other, some instability will set in. And we won’t “meet up in space” awfully well. The above session proves to me that there are ways to reach an understanding, and I think I’ve found them.

NOTE:

What I’ve just written treats ChatGPT as another human being. I don’t accept that for one moment. I recall the old ELIZA program of the 1960s – and I’ve even programmed my own versions of it. Which is as sure a way of grokking what’s really going on as anything I know. Now ELIZA (in its most popular edition) emulated a certain sort of psychiatrist engaging in a talking therapy. The session might go like this:

ME: I don’t want to go on living in a world like this.

ELIZA: You are being negative.

ME: Now Herodotus would say that’s a historically unfounded diagnosis.

ELIZA: Say, do you have any psychiatric problems?

The robot appears to be following my thought processes, but that is a conjuring trick. Its first reply was simply because I’d used the word “don’t”.

In ELIZA’s script there’s a section like this:

NO, NOT, DON'T

You are being negative.

Aren't you being negative?

Don't be so negative.

It takes my prompt word by word, stepping down its script until it finds a matching word, in this case: DON’T. Then it picks a line at random from the three that follow. This stops it being repetitive, which would have it fail the Turing Test.

Its second reply came about because it didn’t find a section to match what I’d typed. So it gave me its stock challenge.

Cinema-goers will recall that in The Terminator, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character had just this way of conducting a conversation with his apartment landlord.

ELIZA is a very simple program. There is no “thinking” going on under its hood, as you and I would understand. But there is intelligence – though people mean different things by that word.

Let’s recall where the word comes from. Latin: (inter + ligere, lectum) – to choose between [alternatives]. And by implication, to use “knowledge” to inform the choice. And that’s precisely what ELIZA does. For ELIZA, knowledge comes as a script.

We’ve since mystified this plain rational concept, to mean something like: that wonderful faculty of mind that sets us human beings above the animals. To which the Bull might justifiably say: “Bullshine!” Likewise the robot.

Now GPT (the engine beneath the hood of ChatGPT – a sort of fancy teleprinter link) is a [finite] state machine, much as ELIZA. It scans your input prompt from left to right, skipping from state to state. What determines the next state is a predetermined probability attached to every pair of states. Calculating that probability is called “training the model” – viz. the Large Language Model, or LLM. The big difference is this: whereas ELIZA had at most a few hundred states (i.e. sections), GPT has billions.

It’s not a difference in nature, but in scale. And with vast scale comes emergent behaviour. But at the end of the day, if ELIZA isn’t really “thinking”, then nor is GPT. Its chattiness is a conjuring trick – an illusion. One which I’m conditioned to resist. Before artificial intelligence (AI) is really useful to me – and not just as a fancy way of consulting Wikipedia – I need to train it to act like a machine again. The sort of machines I’m familiar with.

At last I think I’ve cracked it.

But all the time I recall what Mephistopeles says in Goethe’s Faust when he sees the Homunculus:

Much have I seen, in wandering to and fro,

Including crystallised humanity.