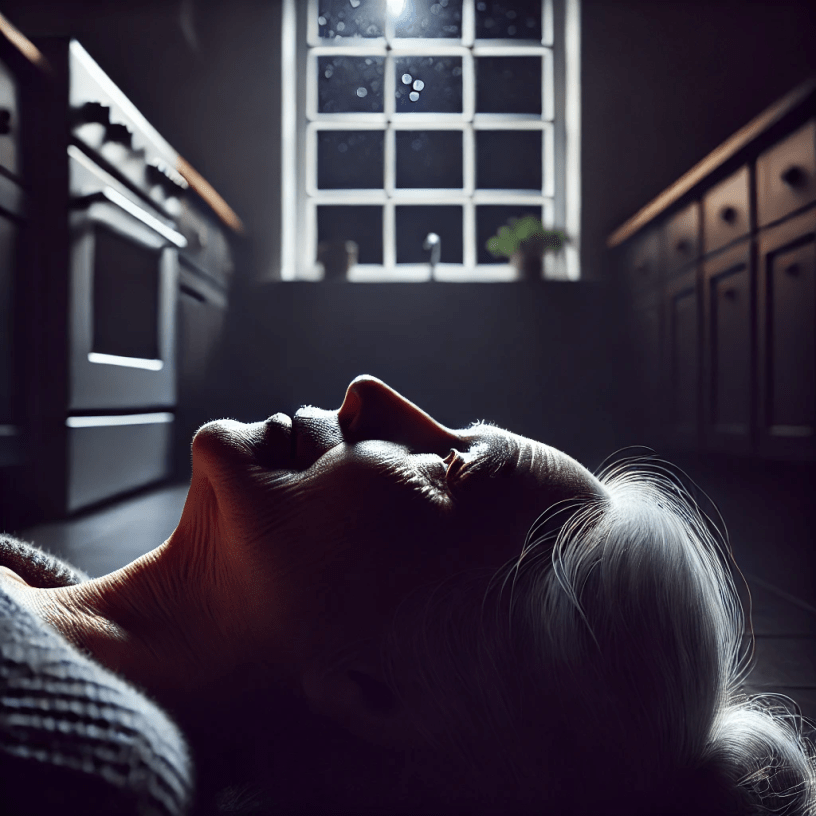

‘If I hadn’t got up to check the gas was turned off, what would I be doing now? Well, not all that different, but it would be in a nice comfortable bed. So what? It’s not at all bad here. Besides, I’ve never spent the night in a kitchen. There’s always a first time, they say. And I can see the window from here, too…

‘The sky is a dark glowing grey and a single star is beaming down into my little kitchen. My children used to tell me the stars were thousands of miles away. Unbelievable! For although I cannot read a magazine these days, I can still see a thousand miles.

‘How much I still have!

‘My children have all left me now. Bill – dear Billy – lost in the War. Margaret’s in America, having a good time. Peter… I haven’t heard from him for years now. Please God that he’s still happy. I know he must be. Surely he’d have written to me if he was in trouble.

‘Life is funny. You bring children into the world, care for them, dry their tears when they fall over… and now there’s nobody left to pick you up when you’re down yourself.’

She could recognise various things about her, but she’d never seen them from this angle before. Straight ahead was indefinite blackness. Her star vanished when she gazed directly at it, but lit up bright as ever when she shifted her gaze. Everything was visible all around her in various shades of ghostly grey. Intangible gas stove and shelves which disappeared every now and then in a spasm of straining to see.

How alert she was! And how loudly that clock had started ticking. Never mind. It wouldn’t keep her awake. It couldn’t – nothing could. She felt so warm and cosy. So comfy and sleepy.

‘How lucky I am! And to think what a job I had trying to get to sleep last night. Now Mabel will come in the morning and pick me up, and she’ll make a cup of tea, and we’ll have a little chat…’

The parish priest, inoffensive, nice little man, fingered his cards nervously. He was trying to catch her eye. Mabel next to her said ‘Two hearts’, but this was rather silly because she had nearly all the hearts in her own hand.

Moloch, sitting opposite Mabel, sniggered obscenely. ‘Have you noticed,’ he said in his sneering voice, ‘how rarely one finds true lovers together? One may love, but how often is that love returned?’

He leered sideways at her and cuddled his cards to himself, gloating. A repulsive young man. He smelt of sulphur and cheap brilliantine and reminded her of someone she didn’t like.

It was Father O’Reilly’s turn. ‘Two spades.’

‘Ah,’ said Moloch. ‘You’ve come to bury us, not to praise!’

The allusion was lost on poor, shrinking Father O’Reilly, who had only just come over from a very uneducated part of Ireland.

‘My turn,’ chuckled Moloch. ‘I’ll go five coshes.’

‘Five hearts,’ she breathed defiantly at the young fellow. His upper lip curled and he seemed to coil back inwardly for a sarcastic riposte of unbearable scorn.

‘Six clubs,’ Mabel interposed quickly, though obviously dismayed at her partner’s bid.

The poor little priest was getting very agitated. He looked pitifully up at her, his eyebrows framing a desperate, hopeless question. Poor Father O’Reilly. He was so ready to help people, but he obviously couldn’t give them what he had not got himself. It wasn’t surprising that he didn’t have the heart to go on.

And Moloch knew it – the swine! This was clear from what he’d said. Now he looked with brazen contempt at the cringing little Irishman as he mumbled something about hearts, then he leaned back in his chair and barked with derision. His eyes, loaded with ersatz charm, were now levelled at her as he said meaningfully, ‘I pass’…

The clock ticked away on the mantelpiece and the silent star shone steadily in the four-square pane of luminous grey. She blinked and took a deep breath and as she did so her lower abdomen ached warningly. It had become hard and uncomfortable all of a sudden. Her back was aching and other regions felt numb.

‘I wonder if I dare turn over. I’d be much more comfortable on my side…

‘Oh!’ A vicious flaming pain scorched up from her lower abdomen as she stirred slightly and she collapsed back with a gasp. She had to screw her face up while the pain slowly drained away to a bearable level. Oh, but it was horrible!

‘So that’s that. I’ll just have to stay like this till morning.’ And she tried to compose herself and settle down to the long hours of waiting… tick… tick… tick… tick… on… and on… and on…

‘I wonder what the time is.’

She couldn’t see the clock from there, only hear it.

That does it! Tomorrow she’d ask Mabel if she knew anyone who had a chiming clock. They’re quite out of fashion nowadays. Surely they’d exchange it for a kitchen clock. It’s old, but it goes very well when it’s on its back. She wouldn’t really miss it… But with a chiming clock you’d have to remember to wind up the chimes. She’d get Mabel to do that.

A chiming clock. How nice…

‘Bill! You’re here! You’re back!’

He was standing there beside her, right beside her, looking down into her eyes. But sadly… oh so sadly. She remembered how he used to look as a little boy when he was just about to burst into tears. He looked like that now.

‘Yes, Mother, I’m back.’

‘My, whatever’s the matter? Have you lost something?’

He looked distracted and didn’t seem to hear the question. ‘Why are you lying down there on the floor, Mother?’

‘Oh, Bill, I am glad to see you. Now please – be an angel and help me up. Oh, you always were such a good boy to your old mother. Your brother and sister have gone off and left me all on my own, you know. Did I tell you?’

‘No, Mother.’

‘Didn’t you hear me? Not in my prayers?’

‘Prayers…’ His voice seemed far off.

‘Bill, my love…!’

He knelt down beside her and gently stroked her forehead. ‘Yes, Mother, you’re all right now. You’re all right! Don’t worry anymore. Not now.’

‘Billy, Billy,’ and her eyes brimmed over. ‘Don’t leave me, please Billy… never again… Billy…’

…Tick… tick… tick… The clock intruded upon her consciousness. What’s the matter with it? Had it stopped…?

‘My God,’ she choked. ‘I’m seeing things. I thought –’

A blank disappointment settled upon her like a shroud. ‘And yet it – it seemed so natural! It just didn’t occur to me… I forgot he’s dead.’

She found she was shivering and she suddenly felt a spasm of cold, like a bucket of filthy water sloshed over her lungs and entrails.

‘I’m going delirious. I’m not going to last the night.’

The utter hopelessness of the situation opened to her like a door. She felt the bitter, soothing draught of despair, wafting the veil from something in her. Mabel wasn’t coming in the morning, she remembered now. How silly of her to hope for it. But it wouldn’t have mattered anyway, even if she had been. She recalled what happened to old Mrs Birdall. She was dead in the morning when they found her.

A sudden impulse and she called out. Her voice deafened her, echoing inside her skull. ‘Help! Help! Oh…!’ She tailed off as her broken pelvis exploded with pain.

The clock ticked on. Not a sound apart from that. There was nobody around. Nobody else was awake in the whole wide world and no one could be woken, either. She tried a little croak of self-pity and realised that her shouting hadn’t been much louder than that. Just a mournful wail.

Her sight grew dim. She barely noticed the silhouette that appeared outside the partly-open window. It took a moment, then it registered… and a rich flood of relief surged through her body. It was Hector!

With a hiss of scraping fur Hector slid through, regaining his feline shape with a tail-erecting flourish. He was here – her saviour! Her only friend in the world now, come in the time of her direst need.

‘Come here, Hector,’ she murmured painfully and made a little sucking noise with her wrinkled lips.

Plonk. He landed on the floor forepaws first and a moment later there was his pointed nose nuzzling into her ear in jerky little sniffs. Her arm sluggishly felt for him and fondled the soft warm fur. Hector purred and curled up by her cheek.

‘Dear Hector,’ she moaned. ‘Dear, dear Hector.’ And she felt she was being lulled by waves and gently rocked under a tropical sky…

It had never been dark night. She had been here all afternoon, lying in the bottom of the pea-green boat, warmed through by the sun, with Hector by her side.

‘Where are we going, Hector?’

‘Far away. I’m taking you away from all that. We’re going to a desert island where we can live out the rest of our days in carefree abandon.’

‘Oh, Hector!’

‘No need to stint yourself for me anymore,’ he waved his black hand. ‘No more saving for my food out of your pension. There’s fish in the lagoon and acres of coconuts filled with milk. No more Kit-E-Kat for me, or for you – we’re in the lap of luxury!’

‘Hector, how clever of you to think of all this.’

‘Not at all. Nothing is too good for you, oh Mistress-mine. The slightest qualm, the slightest discomfort… anything the matter?’

‘My head. I – I’m afraid the rocking and bobbing is making me dizzy. I think I’m going to be seasick…’

‘Let’s go back,’ Hector murmured in her ear.

There she was, back in her darkened kitchen. She felt for Hector but he wasn’t there anymore.

‘Life is funny,’ she said aloud in a croak. She carried on in her mind because it was too much effort to speak. ‘You bring up cats, feed them, care for them – and when you’re down, they go away and leave you in the lurch.’

The nausea which ended her dream came back in a rush. She nearly vomited, but it sank back, leaving intense cold in its place.

She was an icicle, hanging in a forest of gleaming white needles.

Now she was rattling and slithering round a tumbler and whisky was being sloshed over her. It burned through her skin and set fire to her stomach. Then it went out and she cooled down again. Something icy scuttled across her forehead. It was a bead of sweat.

Cold… cold… cold…

Bright, white cold. She puffed a cloud of breath, a dense, white, palpitating cauliflower that floated upwards for a long time before it dispersed. But the passengers sitting opposite her made never a move – they just stared back frigidly.

She bounced up and down on her seat restively, impulsively, and examined her colourful knitted mittens. Ticktockticktockticktock went the wheels of the train as they scampered across the icy rails – and she was tickled to see that the gentleman in the corner had icicles in his beard! In fact all the passengers seemed to have a good coating of hoar frost except herself, young, vivacious and warm-blooded.

The cold air burned her cheeks but it didn’t make them numb. But oh! – her fingers! She wanted to throttle a few of her fellow passengers, just to give her fingers some exercise. The temptation was getting far too strong, so all of a sudden she got up and thrust her way out of the compartment.

The powdery snow was an inch deep in the corridor. The only other person there was a man, stamping his feet and panting every so often. She couldn’t help staring at him. He had no frost on him at all!

He in his turn stopped, cocked his head on one side and gave her an enigmatic look. Quizzical? Playful? She recognised his face, but couldn’t place him.

‘Why are all those people in there covered in frost?’

‘Because, my pretty young nineteen-year-old, they are cold,’ he replied. ‘Inside and out.’

Of course. It was her husband. How young he looked!

‘When did this train journey start?’

‘Oh, years and years ago,’ he answered blandly. ‘They were born frozen and they were brought up like it.’

‘But when is it going to end?’

‘Is it?’ (He did have an exasperating way with people sometimes.)

‘Oh, don’t kid me! Of course it is.’

‘Well, if you say so…’

He laughed. She went up and took hold of his warm lapels. ‘I want to get off!’

He replied soothingly, ‘You will, my dear, very soon. Follow me at the next station, just before we get to the Dawn…’

It was now pitch-black in the kitchen and she was meeting her body head-on in deadly battle, setting her toothless jaw against the magnetic pull of her pelvis, which was poisoning her system into numbness. No! It was not going to reach her brain. She was determined not to drop off. She was going to stay awake, under pain of death.

Ah, she knew what had happened now. She had had a blackout and fallen. Old people’s bones are weak. It was a stroke. Of course it was. The pulsing in her head – the nausea. Were the pelvis and the brain conspiring to kill her? She wouldn’t stand for it.

‘No, Paul. I’m not going to follow you. Not yet!’

Not to fall asleep, under pain of death. But what a fight! She began muttering to keep awake and to shake her head to and fro. Yes, she was shaking it off. She was winning!

‘Oh Mabel, come soon! I can’t hold out for ever…’

It’s Always Darkest Just Before The Dawn. The words formed themselves into a shape. It had a hopeful, mauve sort of colour.

With a thrill she noticed the sky outside the window. Black cloud had swept away her star, but a rent in the cloud revealed a lighter sky behind. Not the intense glow of dark night, but a real colour you could actually see when looking straight at it.

She was home! The Dawn…

Mabel unlocked the door. ‘Cooee, Mrs D. Are you about?’

‘…Oh!’ She rushed into the kitchen and knelt down beside the old lady. ‘Ow, Mrs D! What happened? Are you – ?’

First published in VOLCHIN & Other Stories, by Clark Nida.